I am often asked to analyze historical events to draw parallels and inform our present circumstances. One such event that immediately comes to mind is the hyperinflation that occurred in Weimar Germany from 1921-1923.

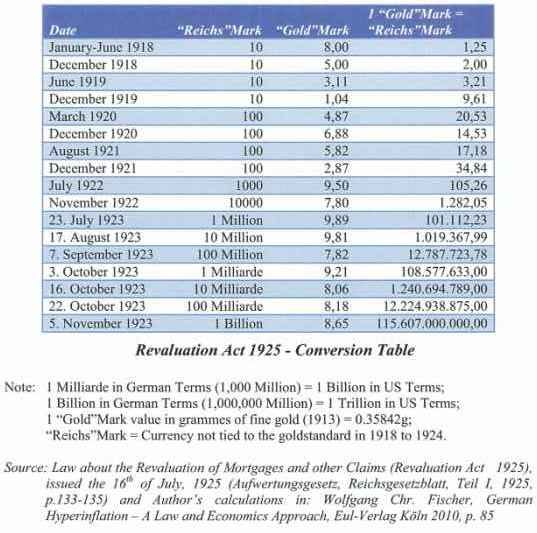

The story of Weimar Germany is familiar to most people, but it is worth revisiting the specifics. Germany took on a great deal of debt denominated in gold to pay for World War I. In order to meet these debt payments, Germany suspended the gold standard and began to print money (from 1918-1920).

This move resulted in the confiscation of purchasing power from its citizens, as their savings were transferred to newly created paper currency to make debt payments.

After losing the war, Germany was saddled with even more debt via war reparations imposed by the Treaty of Versailles in June 1919. For a few years, Germany was able to meet its obligations. However, in 1921, the debt payments became too much, and the government had a choice to make:

default on their international debts

print as much money as necessary to purchase the foreign currency they needed to make their debt payments.

Naturally, the bureaucrats chose the second one. Over the following two years, every person on Earth who held any German marks saw the purchasing power of those assets diluted to zero. This catapulted Germany into the Stone Age for two years, and the inevitable collapse left the country destitute and ripe for populist extremism to scoop up the wounded nationalist spirit and carry it into an even more terrible Second World War.

But what is the most notable element of this quintessential hyperinflation story? It is a minor detail that Weimar hyperinflation was punctuated by sharp bouts of deflation. At first glance, the graph of the inflation rate during that time looks like a parabolic curve straight to the moon. However, upon closer inspection, there were brief dips along the way, periods of deflation, short-lived.

Fast forward to the present moment, and strange economic tides are swirling. For the first time in modern history, we are currently seeing a notable contraction in the US dollar M2 money supply.

This is largely due to banks slowing new lending to a trickle, primarily driven by their risk management duty to maintain a certain ratio of bank deposits to outstanding loans, a ratio recently strained by the exodus of deposits to higher-yielding money market funds.

The net of it is that the M2 is shrinking because of credit contraction. In our credit-based economy where economic growth requires lending through credit expansion, the opposite trend is generally viewed as a leading indicator for a recession on its way.

The other piece of the puzzle that I want to pull in for consideration is the looming debt ceiling crisis. The United States is exceptionally good at saying "yes" to more debt, and neither party actually wants to draw a line in the sand. The true aim is to score political points by pretending to care deeply about the national debt, before inevitably voting to borrow more anyway. The politician's creed: spend now, leave the bill for your successor.

The only uncertainty is how much political brinksmanship will happen before the US takes on more debt. Unfortunately, we're not off to a great start. The US technically already hit the debt ceiling back on January 19th. Since then, the US Treasury has been forced to avoid default through "extraordinary" accounting measures (what would probably be considered "cooking the books" if done by anyone else).

This suggests that investors are increasingly worried about the US government’s ability to pay its bills in the very near future. And if the US were to default on its debt, the ripple effects throughout the global financial system would be catastrophic.

The combination of a shrinking M2 money supply and the looming debt ceiling crisis creates a potentially dangerous situation for the US economy. The reduction in the money supply puts downward pressure on economic growth, while a default on US government debt would send shockwaves through financial markets around the world.